On the surface, it would appear we are a changed society. Supposedly more aware than ever of our impact on the environment, our media habits also suggest that we’re interested enough to spend our spare time immersing ourselves in the natural world. Planet Earth II amassed 12.26 million views (or 40.9% of the television viewing public) for its first episode in 2016, a vast increase from the previous record of 9.72 million views of Frozen Planet in 2011. Sir David Attenborough urged: “It’s surely our responsibility to do everything within our power to create a planet that provides a home not just for us, but for all life on Earth.” He’s right, of course, but although the message was heartfelt, it does not, as Rebecca Broad points out in issue 2 of New Nature Magazine, “do everything within its power to encourage a home for all life on our planet.”

It’s not the first time this style of programme has been criticised: in his controversial article for The Guardian, Martin Hughes-Games suggests “these programmes are still made as if this worldwide mass extinction is simply not happening”. Nature’s appearance and ability to survive is, according to Hughes-Games, portrayed with rose-tinted glasses. And since we are able to see nature on our screens – often zooming microscopically, slowing down time to observe the intricacies we would never normally see – we no longer find the need to explore it ourselves, and realise that it's still in danger of collapse. Nature becomes an alien concept, something we remain distinct from, as we voyeuristically consume it in any form other than reality.

In its manifesto, The Dark Mountain Project (a network of writers, artists and thinkers who have "stopped believing the stories civilisation tells itself") notes that “the very fact that we have a word for ‘nature’ is evidence that we do not regard ourselves as part of it,” and this seems to be the crux of the problem. Our tendency – and I am by no means immune to this – is to see nature as something to inhabit, to conquer, to observe, to comment on. It’s rare that we see it as a part of our very being, as something that is embedded in our daily actions and thoughts without question, and with the media disassociation that takes place so frequently, it's not altogether surprising.

If, as the founders of Dark Mountain suggest, we are undergoing an ecocide (and for my part I’m convinced we are), then in destroying life on earth, in destroying nature, we are destroying ourselves. In our attempts to prevent this destruction, to replace fossil fuels with wind-power and solar panels for example, we are aiming to save industrial civilisation, rather than the environment. Though I don’t believe switching to these eco-alternatives is a negative thing – they enable health, education, sanitation; concepts that undoubtedly are achievements of the modern world - it’s both interesting and essential to consider how we’ve managed to develop a civilisation so inherently disconnected from the world around us.

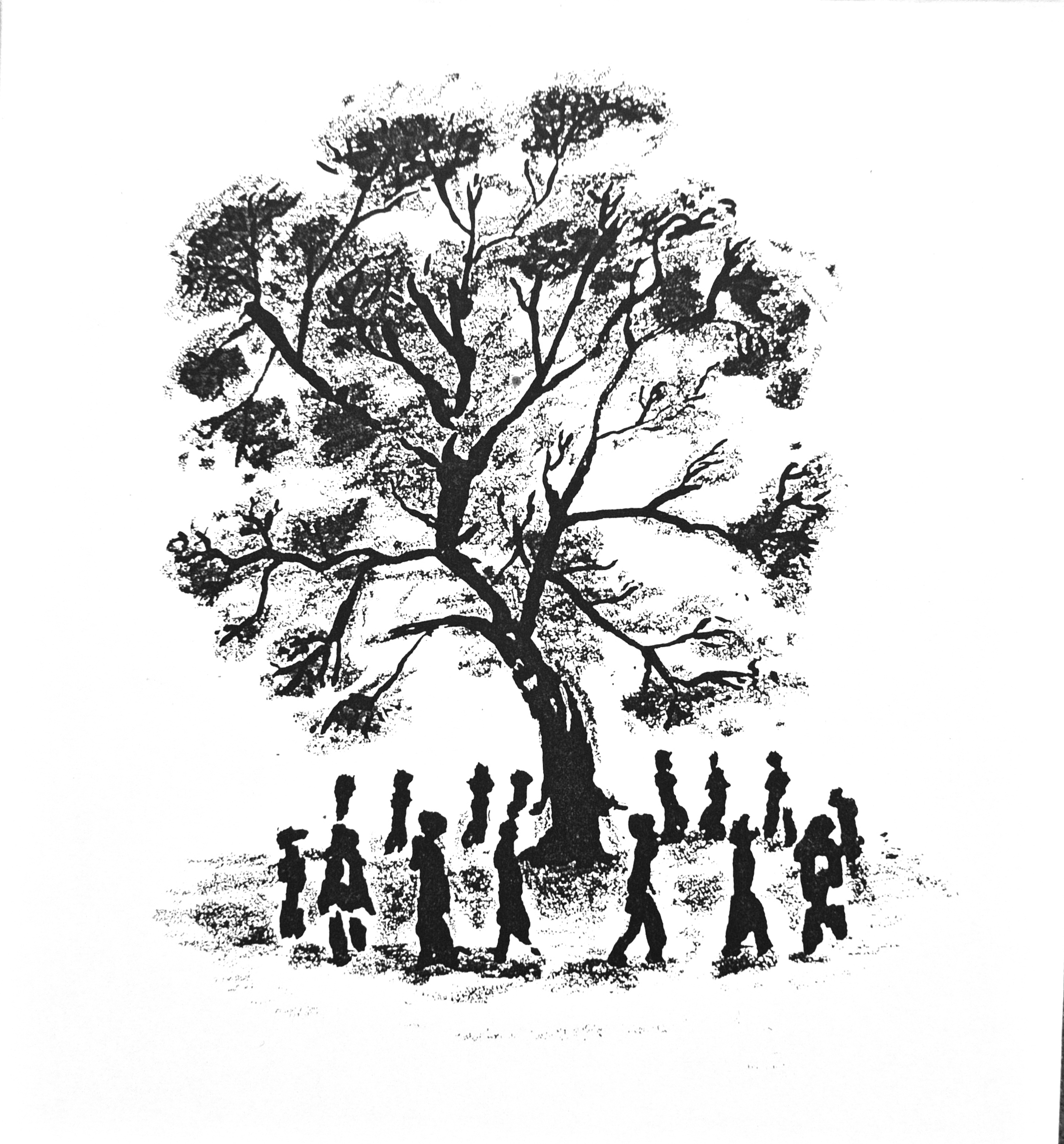

Avoiding a descent into hopelessness, Satish Kumar suggests a solution: “We are members of one Earth community and need a new trinity that is holistic and inclusive, that embraces the entire planet and all species upon it. So I propose a new trinity of soil, soul, society.” In order to reconnect with nature in a way that allows us to be a part of it, we must first respect it and what it offers, taking time and care to be in nature, noting its changes and its powers, as well as its ability to join our society together.

He ends: “If we can have a holistic view of soil, soul and society, if we can understand the interdependence of all living beings, and understand that all living creatures – from trees to worms to humans – depend on each other, then we can live in harmony with ourselves, with other people and with nature.”

To reconnect nature and civilisation is to change our perception of the ‘outside’ world. Let’s remove this concept of the unknown, the alien, the ‘other’, and truly become one with the earth.